Luke Blaidd

The Hanes LHDT+ Cymru blog normally focuses on LGBTQ+ Welsh history past, however, I would like to introduce the potential Welsh language history of the future: Gender neutral pronouns.

The inclusion of gender neutral pronouns in everyday Welsh is hugely historic for the language and is already underway in pockets of Welsh speaking LGBTQ+ communities. Many LGBTQ+ Welsh speakers have been testing the boundaries of language and breaking the mould in everyday speech. As part of my dictionary, I will be including a segment on pronouns- so please do watch out for that!

For now, though, I would like to invite you on a journey into the wonderful world of weird Welsh pronouns. Greater awareness of these pronouns can really help make someone who uses them feel wanted and included in Welsh speaking communities near you and afar. As is tradition with my blogs, I must squeeze in a reference to ancient mythology somewhere. So, today’s mythology metaphor is that searching for and documenting Welsh neopronouns is like descending into the depths of Annwn, into a deep and great unknown- emerging into the realm and finding all the language you needed to express yourself fully, truly, brilliantly and wholly.

A Rhagwennau Rhyfedd* Guide to Welsh Pronouns

(* ‘Weird Pronouns)

Binary Pronouns:

Binary pronouns are the most common pronouns and include ‘he/his’ and ‘she/hers’ in English. They’re the most familiar pronouns to most, existing in the context of binary gender. E.g., boy and girl, man and woman, male and female. The following is a brief and non-exhaustive overview of how these pronouns work in Welsh. Of course, there are many more grammar points around each pronoun, but for now, this is a no-frills crash-course in Welsh pronouns:

E(f)/Ei-

‘E(f)/ei’ is the equivalent of ‘he/his’ in Welsh, which denotes the masculine subject and possession in a sentence. For example, in English you may say ‘it is his jacket’ or ‘he is late for the bus’. Welsh has two main linguistic contexts in which certain parts of grammar may be slightly different. ‘E(f)’, meaning ‘he’, is used in formal or written contexts, while the equivalents ‘fe’ or ‘fo’ are used in informal or colloquial contexts. In addition to this, the colloquial forms differ in different parts of Wales. ‘Fe’ is generally used in South Wales while ‘fo’ is generally used in North Wales. You may see variations on ‘ef’ as well, it is common to drop the ‘f’ to just ‘e’, hence why in this blog it is written ‘e(f’)’. All of these variations, however, use the same possessive pronoun ‘ei’.

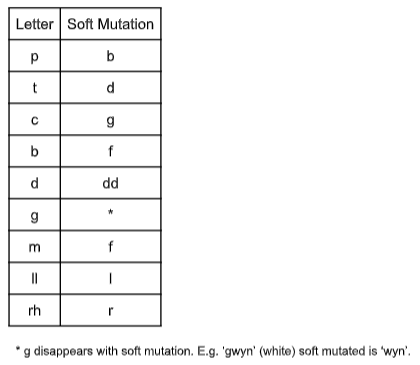

‘Ei’ indicates possession and is analogous to ‘his’ in English. However, as will be explained later, ei is also used for ‘hers’ too. You can figure out if an ‘ei’ refers to ‘his’ or ‘hers’ by looking at the mutation it causes on the noun which follows it. There are three main mutations in Welsh in which the first letter (or letters) of a word change to aid in the flow of a sentence. They are: Soft Mutation, Nasal Mutation and Aspirate Mutation. Masculine ‘ei’ triggers a soft mutation in Welsh. Soft mutations affect the letters p, t, c, b, d, g, m, ll and rh. You can see the changes in the table below.

In the possessive, only nouns with feminine grammatical gender mutate. For example, the word ‘cath’ (cat) mutates to ‘gath’ because it is a feminine noun. While ‘ci’ (dog) does not mutate as it is a masculine noun. Therefore, if you were to take all of this and put it together, the sentence ‘Mae ei gath yn gyflym’ (his cat his fast) is clear that it is his cat that is fast and not her cat that is fast. A few other sentences: “Beth yw enw e?”- What is his name? “Siaradwch ag ef”- Talk to him.

Hi/Ei-

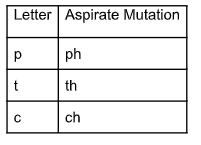

‘Hi/ei’ is the equivalent of ‘she/hers’ in English, denoting the feminine subject and possession. In English you may say ‘her tea is going cold’ or ‘she’s wearing a hat today’. Unlike ‘e(f)/ei’, ‘hi/ei’ is used in both formal and informal contexts. As mentioned before, both binary sets of pronouns in Welsh use ‘ei, but they can be told apart by their mutations. For feminine ‘ei’ the mutation used is the aspirate mutation. Aspirate mutations only affect the letters p, t and c, as explained in this table below:

Therefore ‘Mae ei chath yn gyflym’ shows it is her cat that is fast. Other sentences include: “Beth yw enw hi?” – What is her name? “Ble mae hi?- Where is she?

Neutral Pronouns:

The term ‘neutral pronouns’ is most often used in reference to the use of singular ‘they/theirs’- but there are other pronouns that have been created (in multiple languages) which are also gender neutral, but not necessarily analogous to the standard singular ‘they/theirs’. These other pronouns are usually called ‘neopronouns’ (literally, ‘new pronouns’). Neopronouns have been around since the 1800s. Most famously, the gender neutral pronoun ‘thon’ in English dates as far back as 1858! Other neopronouns include ‘ze/hir’- used by the writer Leslie Feinburg. Welsh has some neopronouns too, mostly created between the 1990s and 2020s. Before we look at Welsh neopronouns, I would like to introduce the Welsh equivalent of singular ‘they/theirs’ and how it has developed over the years:

‘Nhw/Eu’-

‘Nhw/eu’ is the simplest form of singular ‘they/theirs’ in Welsh. In fact, ‘nhw/eu’ is the plural form of ‘they/theirs’ in Welsh. When referring to someone in the singular, most users of ‘nhw/eu’ use context to key others into that it is being used in the singular. The reason why ‘nhw/eu’ signals plurality is because of the possessive ‘eu’ (pronounced the same as ‘ei’). ‘Eu’ is the plural possessive, referring to something which belongs to a group of people. In English you might render this like so: ‘At Thom and Andrew’s house, aren’t their chairs in the shed?’. Because of the plural associations of ‘eu’, many ‘nhw’ users prefer to use ‘ei’ (like with ‘e(f)/ei’ and ‘hi/ei’).

‘Nhw/Ei’-

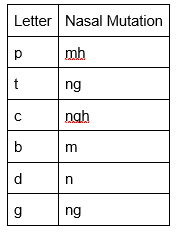

Functionally the same as ‘nhw/eu’, but uses the singular possessive pronoun ‘ei’. Some choose not to mutate after ‘ei’, however, some ‘nhw/ei’ users will use the third and final mutation, the nasal mutation, to signal neutral gender in the possessive. The nasal mutation is not currently assigned (officially) to a gendered possessive like ‘e(f)/ei’ and ‘hi/ei’. The nasal mutations are listedd in this table below. It affects the letters p, t, c, b, d and g:

Therefore, ‘Mae ei nghath yn gyflym’ indicates that it is their (singular) cat that is fast. Other examples include: “Beth yw enw nhw?- What is their name? “Mae ei ngwallt yn hyfryd”- Their hair is lovely.

‘Ŵ/Ei’ (ŵ)-

The next few sets of pronouns are further variations on ‘nhw/ei’. Various pronouns have been suggested in the past few decades and ‘ŵ’ (pronounced like the ‘oo’ in pool) is one of them. ‘Ŵ/Ei’ as a set of pronouns dates back to May 2020, when a petition was submitted on the 6th of May to the Welsh Senedd. According to the petition submitter, the pronoun ‘ei’ could be used with ‘ŵ’ but would cause no mutation. The petition submitter also covers a few other grammatical points, such as gendered professions and prepositions. In order to keep this concise, we will just focus on the vocative and possessive for now. Using the grammar rules suggested by the petition submitter, ‘ŵ/ei’ would look like this: “Beth yw enw ŵ?” – What is their name? “Mae ei llyfr yn hen iawn”- Their book is very old. And of course, ‘Mae ei cath yn gyflym’- Their cat is fast.

‘Hw/Ei’-

This is another variation on ‘nhw’ I have encountered in my research. In this, the initial ‘n’ of ‘nhw’ appears to be dropped. Something I like about this is that ‘hw’ is made up of two letters, like ‘e(f)’ and ‘hi’, so it matches the traditional length of a third person pronoun in Welsh. As with ‘nhw/ei’ it functions the same, just with one less letter. For example: “Beth yw enw hw?”- What is their name? “Mae ei nghardd yn fawr”- Their garden is big. ‘Mae ei nghath yn gyflym’- Their cat is fast.

Neopronouns:

And now, we move onto the neopronoun section of this blog. These two sets of pronouns are the only ones on this list that I have had a hand in creating. As ever, these are purely suggestions. It is always up to you whether you would like to use them or not. ‘Hwy/Ei’-

This set of pronouns is arguably related to ‘nhw/ei’, though in testing these pronouns out to see if they could become potential neopronouns in Welsh, I have grown rather fond of them. So much so to the point that I ordered a custom neopronoun pin from queerlittleshop with them on!

‘Hwy’ as a pronoun technically already exists in Welsh. Remember the formal/informal context I mentioned earlier in the blog? ‘Hwy’ is the formal written version of ‘nhw’. But these days it is exceedingly rare to see ‘hwy’ at all, as it behaves almost like an archaism (a fancy word for old words) at times. The online dictionary Gweiadur also notes that it is the archaic form usually only seen in formal writing. This, I feel, is why it works so well in informal contexts to denote a neutral person in the singular. Because of its exceeding rarity, it is not likely to be confused in everyday speech for another pronoun. My personal preference also lies in that ‘hwy’ has a nice ‘wy’ sound at the end, reminiscent of masculine ‘e’ and feminine ‘hi’. While ‘nhw’ is a very versatile pronoun, the ‘w’ sound at the end can clash with other ‘w-vowel’ sounds frequently found next to pronouns, such as ‘enw’ (name). Since Welsh as a language prizes linguistic flow, ‘hwy’ complements the existing pronoun sets of ‘e(f)’ and ‘hi’ quite well. To the ear, ‘beth yw enw e’/’beth yw enw hi’ and ‘beth yw enw hwy’ go well together do not interrupt the flows of sentences. While sentences like ‘beth yw enw nhw’, while usable, is a little more clunky in this regard to me. Here is how ‘hwy/ei’ might be used: “Ble mae hwy?”- Where are they (singular)? “Mae ei nghastell yn oer iawn!”- Their castle is very cold!

‘Sê/Sîr’-

And finally, these pronouns were created on the 21st of August 2022 to help a friend of a friend localise a set of English neopronouns to Welsh. The person uses ‘ze/zir’ pronouns, a set of neopronouns created around the late nineties by several people independently of each other. Though one high-profile instance of them is in trans author Kate Bornstein’s 1998 book My Gender Workbook. They are said to be based on the German pronoun ‘sie’. In English, the pronouns would be used like this: “Ze is looking lovely today”. “It is zir jacket ze left on the chair”. “Will ze be on a bus?”. But the challenge was localising ‘ze/zir’ to Welsh without compromising the stylisation and the meaning that these pronouns had to the user. First there was the issue of the letter ‘z’ not existing in the Welsh alphabet. Instead, ‘s’ is used to approximate the ‘z’ sound in Welsh. However, changing ‘zir’ to ‘sir’ creates the obvious problem that ‘sir’ in Welsh means ‘county’. Unwilling to compromise on this, I looked at them again. ’Z’ could not really be used as it doesn’t appear in the Welsh alphabet, but equally there can be no ‘s’ in front of ‘ir’ as that spells ‘sir’.

But then it hit me; the vowels in ‘ze’ and ‘zir’ are closer (to my ear) phonetically to longer vowels than to shorter vowels. Therefore, the stylistic orthography and sound of the pronoun could be represented by a ‘to bach’ (a circumflex) on both the ‘e’ and the ‘i’. And thus, ‘sê/sîr’ was created.

But how would ‘sê/sîr’ work in Welsh?

As ‘sê/sîr’ are neopronouns and not repurposed plural-pronouns-turned-singular like ‘nhw’ or ‘hwy’, fitting them into the Welsh language has more challenges and sticking points. However, it can be done.

As with the examples above, I will only be using the possessive as an example. I will also use the nasal mutation to indicate possession as with ‘nhw’ and ‘hwy’ to keep things simple. Because ‘ze’ and ‘zir’ are formulated for an English syntax, some adjustment is needed to introduce it to a Welsh syntax. The same way that ‘hi’ can mean both ‘she’ and ‘her’ in Welsh, ‘sê’ could be used to mean both the nominative and the possessive. While ‘sî’n’ (‘sîr’ + ‘yn’) could be used as a compound pronoun- not too dissimilar to how ‘hi’n’ is used in Welsh to mean ‘she is’ (‘hi’ +‘yn’).

Without further ado, what could sentences with ‘sê/sîr’ in look like in Welsh?

“Mae ei nhad yn dal” – Ze’s dad is tall. “Mae sî’n oer” – Ze is cold. “Beth yw enw sê?” – What is Zir name? Of course, as with all of the pronouns outlined above, some of them are very much in the rudimentary stages of their development- which means they need help to gain more visibility and usage in the future so that any kinks in adopting these pronouns can be worked out.

With thanks to Hanes LHDT+ Cymru for hosting this blog!