by Syd Morgan

In December 1971, Plaid Cymru’s monthly newspaper, Welsh Nation, published a letter from Cardiff Gay Liberation Front. Its content was an attempt to fuse the demands of the GLF with those of the Party’s aims. It had been written by Stuart Neale, active in both organisations and this narrative chronicles his attempt to co-exist within both political spheres.

In 1972, he became the first openly gay man to stand in an election as a Plaid Cymru candidate. Yet, despite his many previous election campaigns for the Party – from 1967, he contested seven elections at district, county and parliamentary level in rural Monmouthshire – and his prominent national status within it, Neale’s out status while also a Party activist was not a positive experience. Seen through the lens of the acceptance of gay liberation within electoral politics then, his experiences illustrate the perceived conflict between a political party’s electoral focus and its coming to terms with an emerging social movement which was not prepared to be invisible.

Neale grew up in Penarth, joining Plaid Cymru at the age of seventeen. He worked in Cardiff Central Library, then took a course at the Welsh College of Music & Drama. Thereafter, he was “in the theatre for three years [but] finding it difficult to get work on the stage [and] determined not to be forced to leave [his] own country in search of work, joined the Forestry Commission”. Neale gradually came to terms with his sexuality; his mother, however, was not reconciled. When he first revealed it, he was referred to a psychiatrist who, unlike many at the time, was not unsympathetic to his reality. He remained closeted except with close friends. Even after the advent of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, gay men still experienced the fear of police intrusion. In fact, there was a “tripling of convictions of men for homosexual behaviour in what were defined as public places”. He says this fear was present, whether they meet privately, such as the Castle Bar in Cardiff’s Angel Hotel, Rob’s Bar in the Royal Hotel or the Red Cow in Merthyr Tydfil, or even in public as groups of friends at large gatherings such as rugby internationals.

Neale moved to Abergavenny in April 1965 to take up his new employment. The town had seen the conviction of over twenty gay men in 1942, leading to a suicide and two further attempts.* Neale knew one of the surviving victims and says the scandal still hung over Abergavenny. He soon became politically active. As a forestry worker, he joined the National Union of Agricultural & Allied Workers (NUAAW) and was elected in 1966 as shop steward of its Mynydd Du branch. This gave him a seat on Abergavenny Trades Council. In 1966, Gwynfor Evans was elected as Plaid Cymru’s first MP. In the post-Carmarthen

euphoria, Neale became the Party’s first candidate to contest an election for Abergavenny Borough Council, in May 1967. With an endorsement from Evans, Neale received nearly 25% of the vote. The result which reportedly “caused a surprise [generating] the biggest reception of the night [and a] resounding ovation from Party supporters, who sang with him the Welsh national anthem”. As the Party rapidly expanded, a Monmouth district committee and Abergavenny branch of Plaid Cymru were formed, both with Neale as secretary. He also captured the zeitgeist of the new era of Party organisation following the

appointment of modernising officials at its Cardiff headquarters. Neale was an early beneficiary of their innovative campaigning techniques.

In May 1968, Abergavenny Plaid Cymru was credited with generating “a lively election”. Neale gained nearly 30% of the vote, coming second. At his third attempt in May 1969, the Abergavenny Chronicle’s analysis was encouraging: “. . if his past record has anything to go by he will now manage to slip home [and] voters disenchantment. . could give Plaid Cymru their first Borough Council seat”. This time he came last in a triangular poll with less than 20% of the vote.

At the same time, Neale was the Party’s national agriculture spokesman, and was asked to use his powers of oratory to win votes for the leadership at national Party forums. He was

also in demand as a guest speaker at Party events across the country. During 1970, Neale contested no less than three elections. For Monmouthshire County Council in April, he gained over 40% of the vote; standing for Abergavenny Borough Council in May, he achieved his highest yet, over 45%. In the June 1970 UK general election, Neale broke more new ground as the Party’s first candidate for Monmouth constituency; that year was the first time Plaid Cymru contested all parliamentary seats. Neale ran what is generally considered to be a good campaign with a small, enthusiastic band of activists. The Party’s national vote share was 11.5% and its first and only MP, Gwynfor Evans, lost his seat. Although Monmouth polled the lowest percentage nationally, Neale reported, “Morale is running very high . . Party workers . . learned a great deal . . New support had been gained .. and the organisation strengthened”. So after four years of intense campaigning in new territory for Plaid Cymru, taking on a national role, being in demand as a ‘personality’, and his trades union activities, Neale clearly established himself as a high-profile and able political figure, demonstrating a personal flair for generating favourable press coverage and creating a sustained interest in the Party’s activities and policies.

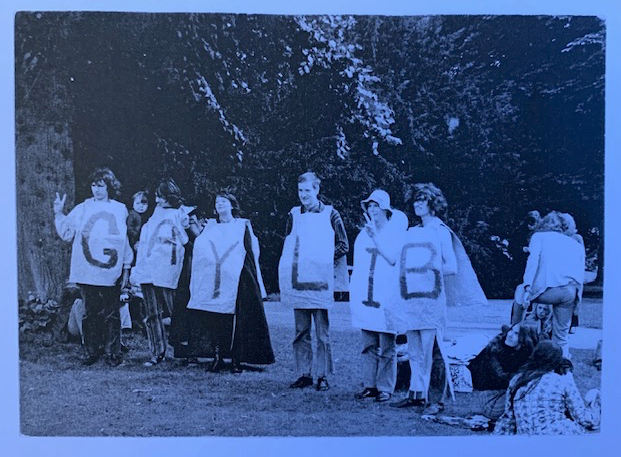

Neale came out as gay within Plaid Cymru after the 1970 general election and, afterwards, the NUAAW. This, he says, drew little obvious adverse reaction from members, nor seemingly within the town (with the usual few homophobic exceptions). Significantly for what was to follow, he started to combine his Plaid Cymru rôles with activism for the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). Neale joined its Cardiff branch, founded by Howard Llewellyn, in July Unlike many members who were reticent for a myriad of personal reasons, he became publicly active in its cause from the beginning, using the same campaigning skills and confidence he had learned and developed in Plaid Cymru. GLF campaigners, including Neale, were visible on the streets. A few joined the rear of another protest march on Saturday 14th August 1971. Through a loudspeaker they urged “Saturday shoppers” to “End discrimination against homosexuals”, “Come to Gay Lib at RIB”, and “Protect freedom of speech, protest against the Oz trial”. People’s reactions varied from “shell-shocked” to “Hey, look, its Gay Lib”. Even “some of the reporters were asking ‘What’s this Gay Lib thing, then?’” After the march, twenty people held a ‘gay day’ within Cardiff’s Bute Park. Neale wore a tabard displaying the ‘L’ of a six person GAY LIB tableau. This was, arguably, Wales’ first public manifestation of gay rights activism.

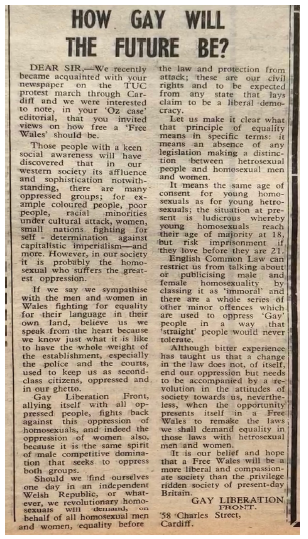

That August, Cardiff GLF organised a letter-writing campaign for reform of the Sexual Offences Act by equalising the age of consent; Neale wrote to Monmouthshire MP, John Stradling Thomas, whom he’d opposed as Plaid Cymru candidate the previous year. That letter is both personal and political: “I hope it will come as a surprise to you to learn that I am a homosexual. I have recently become involved in the Gay Liberation Front and my involvement in GLF has given me the freedom to admit what was once a desperately hidden guilty secret”. On the issue of coming out, he reveals “I, for instance, am still discreet in Abergavenny and district in order not the embarrass my family; otherwise, I do not hide my homosexuality”. On the main point of the GLF campaign, Neale asked “Would you therefore support amending legislation to reduce the age of consent for male homosexuals to that for heterosexuals; or more positively would you initiate such amending legislation?” Maintaining his public campaigning momentum, in September 1971, Neale was one of three Cardiff GLF members interviewed by South Wales Echo journalist Ken Follett. Follett wrote a large, sympathetic article headlined Why Andrew feels like a leper . . . It commenced “Andrew S —— is a tall, fairly hefty forestry worker. He has short hair and is well-spoken. He is aged about 30, a bachelor, and lives with his mother in a village in Monmouthshire. He is also a homosexual”. While anonymised, the vivid headline would have attracted particular attention in this large-circulation newspaper. The personal description would not have made it too difficult for people who knew him to identify Neale. Certainly, members of the NUAAW saw it. Although lesbian, Ruth J —-, and Howard Llewellyn are mentioned, the bulk of the facts and opinions are attributed to “Andrew S—-“. Combining his Party and gay activism, that November, Neale informed Cardiff GLF that “he was writing an article about GLF for the Welsh Nation”. The newspaper had welcomed the successful Appeal of Oz magazine against the original sentencing of its three editors and invited readers’ views on “how free the ‘Free’ Wales should be”. Neale’s lengthy response, How Gay Will The Future Be? imagined a Wales quite different from then-Britain. It also demonstrated the advanced thinking of GLF ideology and Neale personally with an intersectional approach within the broad spectrum of contemporary liberation movements.

Notwithstanding his attempt to combine his political passions, things had changed for him. His name was not listed amongst the 1970 parliamentary candidates reported in the Welsh Nation to be speaking at “Plaid Cymru’s first major rally” in Monmouthshire in February 1971, nor did it appear in the newspaper again that year. In 1972, when Llewellyn and he addressed Swansea University Socialist Society, Neale “confessed that he felt obliged to withdraw from standing as a prospective parliamentary candidate because of the embarrassment it would cause to the party”, a public reference to the tension he felt from being active within both party and gay politics. Neale says that it was a conscious decision on his part as he did not wish to damage the cause of independence. Plaid Cymru’s Dafydd Williams recalls Neale visiting Party headquarters to say that he was withdrawing from Plaid Cymru in the light of his experiences, and of trying to persuade him to stay engaged. Certainly, three months after the Swansea meeting, Neale spoke for the Party at a meeting which attracted a large audience in a mock election at Monmouth Grammar School.

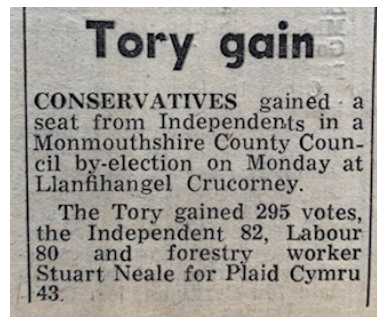

Despite these tensions and personal disappointment, political circumstance and a sense of duty drew Neale back into the electoral arena. He’d moved from urban Abergavenny to rural Pandy by October 1971. The death of the incumbent councillor led to his volunteering to contest the Monmouthshire county by-election in July 1972. After he’d stepped forward, he heard indirectly that ‘someone wanted this stopped’. Neale recalls it was only through the intervention of the Party’s Chairman, Phil Williams, was his candidature approved. But even after ratification, his campaign was virtually abandoned by the Party, causing him to make the final break. Only one other member accompanied him to the count. He gained 8.6% of the vote and fourth place. The ‘abandonment’ narrative seems confirmed by the miniscule election report in the Welsh Nation, in contrast to its more detailed reporting of other council elections during this period.

Whatever the causes, “in the early 1970s, [Neale] stopped coming to Party meetings”. His out status and gay activism combined with electoral politics reveals the Party’s attitude in general. At the time, members’ reactions seem to have ranged between the extremes of homophobia (probably a minority), a wider nervousness about ‘promoting’ gay rights at a difficult time for it electorally (it had no MPs between 1970 and 1974), and a minority of equality supporters such as Phil Williams. This default caution proved to be characteristic of its approach to queer equality for many years. Neale’s experience seems to be its first known manifestation. This ‘studied hidden-ness’ even persisted despite the Party formally endorsing an explicit anti-discriminatory policy toward ‘sexual preference’ in 1978, the first UK parliamentary party to do so.

As a pioneer, Neale was an early recipient of Party fears and prejudices and felt personally and politically abandoned. This dilemma was not uncommon amongst GLF activists. In a critical analysis of the movement’s ideology, Simon Watney writes, “At the time, it seemed as if a choice had to be made between a total commitment to a specifically gay politics, or else to a traditional left party framework in which issues of sexuality could not possibly be raised with the urgency they required”. Faced with negativities, Neale’s life with his new partner and a welcoming engagement with the strengthening gay rights movement, offered a more personal and satisfying outlet for his political dynamism and skills. After the GLF fractured under internal disputes, he was active in the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE), initially in Cardiff and, later, Hereford. This was more a social, counselling, and befriending service, rather than like the GLF, trying to “create a social and political movement”. He used his self-confidence and empathy to support other gay men.

At the same time, he continued his NUAAW work, where he observed institutional male chauvinism; the patronising attitudes to women he saw made him realise that “our fight was the same fight as women’s”, principles consistent with his Gay Future message. Neale’s trade union work was widely recognised in 1976 with his election to membership of the UK Agricultural Training Board and in 1982 as an employee representative on the European Commission’s social partnership Joint Committee for Agriculture. The Party lost an articulate, forthright activist who could command media attention, an effective local leader,

an agricultural policy expert and a trade unionist of growing influence. These were all political spaces in which it needed to make advances. Party stalwart Huw Evans, who knew Neale throughout this period says he was “politically astute and able’ and that after he withdrew, the local party was “rudderless”. Howard Llewellyn similarly recalls his political talents and campaigning strengths. And beyond what was then accepted as conventional politics, Plaid Cymru did not use the potential of a high profile activist who was – perhaps uniquely at the time – simultaneously in the forefront of the growing gay liberation movement. This missed opportunity occurred when the Party itself was becoming increasingly visible and influential, and part of the wider equality movement for women and other minorities. Although Plaid Cymru later corrected this omission, its potentially gaining new supporters was interrupted. Stuart Neale himself re-joined Plaid Cymru in 1997 and is again active.

© Syd Morgan, 2022

*For more on the Abergavenny case see Will Cross’ book The Abergavenny Witch Hunt: An Account of the Prosecution of Over Twenty Homosexuals in a Small Welsh Town in 1942 (2014)